Tug of War

It’s the small things in life that are the big things.

John Wooden

Firstly, do we really know what a short bowel syndrome (SBS) is?

Luckily, we have a definition from the WHO ICD-11: “SBS is defined as the clinical feature associated with a residual small bowel in continuity shorter than 200 cm. The presence of clinical features of SBS notwithstanding a residual small-bowel length >200 cm is defined as “functional SBS”.

In this post, we will focus only on patients who have a short bowel syndrome associated with intestinal failure.

SBS is a fairly unknown pathology, and so its frequency and prevalence; many of the patients are “unknown” to have SBS, and we have no registry of these patients, but we have a few ideas about it: ⅔ of the patients with intestinal failure is due to SBS, accounting for approximately 1.5-34 cases per millions of inhabitants worldwide. Moreover, 60.7% of these patients are women!

But what are the most frequent causes?

- Mesenteric Ischemia: 26.7%

- Crohn’s disease: 27.1%

- Radiation enteritis: 6.3%

- Post-operative complications: 16.7%

Basically, as surgeons, we are mainly responsible for this pathology (if we want to see the numbers in this way).

From the 2023 ESPES guidelines, it is described how SBS are divided into 3 types:

- SBS-type 1: end-jejunostomy/ileostomy; 60% of the cases

- SBS-type 2: jejuno-colonic anastomosis, where the remnant jejunum is in continuity with part of the colon, most frequently the left colon; 30.9% of the cases

- SBS type 3: jejuno-ileo-colonic anastomosis with ileo-cecal valve and the intact colon in continuity, 9.1% of the cases

From a management point of view, the presence of a functional colon is of extreme importance thanks to its capability of production of Short-Chain-Fatty-Acid which self-regulates the proximal small bowel to increase the absorption of macronutrients. Meaning we can divide and manage patients in just 2 categories, patients with colon (Types 2 and 3), and patients without it (Type 1).

We have 3 steps for the management of an SBS patient: nutritional therapy, pharmacological therapy, and surgery. We will try to review these and not be too boring!

Nutritional Therapy

There are a few general advice for patients with SBS regardless of the type they have.

- SBS patients should consume regular whole food diets, and they are to be encouraged to compensate for malabsorption by hyperphagia

- Patients may use enteral feeding support

- Enteroclysis should be used asap, using manual or automatic pumps

For Type 2 and 3 patients (colon present):

- A higher carbohydrate (60%), lower fat (20%) diet is preferable in SBS patients with colon in continuity in order to increase overall absolute energy absorption (the downside is the colon will be more prone to create gases);

- Oral fiber supplement is not suggested, the colon will self-regulate water absorption, and the use of pectin may reduce the creation of short-chain fatty acids.

For type 1 patients:

- Oral food can consist of any fat: carbohydrate ratio, provided that it has a low mono- and disaccharide content;

- Oral fiber supplement (Pectin 4g or others) is suggested in order to gelatinize the stools;

- Patients with type 1 SBS (end jejunostomy) can use salt liberally and restrict the administration of oral fluids in relation to meals (AKA, drink distant then food intake);

- If dehydration or sodium depletion occurs, an isotonic high-sodium oral rehydration solution to replace stoma sodium losses should be used;

- If a high-output jejunostomy is present, the oral intake of low-sodium fluids should be limited, both hypotonic (e.g. water, tea, coffee, or alcohol) and hypertonic (e.g. fruit juices, colas) solutions in order to reduce the stoma output.

Pharmacological Therapy

1 – H2-receptor antagonists or PPI (Omeprazole 20mg twice a day) may be used to reduce fecal wet weight and sodium excretion, especially during the first six months after surgery.

2 – Somatostatin and the somatostatin analog (octreotide) have been shown to reduce ileostomy diarrhea and large volume jejunostomy output in several case series. In some patients, these pharmacies are not effective, with almost no reduction of the jejunostomy output after 3-4 days. In these cases, it is better to remove the drug. Octreotide could also be added to the TPN bag, making it easier for the patient. The downside of Octreotide is severe hypoglycemia during the treatment, make sure to check the patient regularly!

3 – Loperamide is the cornerstone drug in these treatments. It is believed to inhibit the peristaltic activity of the small intestine and thereby prolong intestinal transit time. In general, loperamide 4 mg given three to four times per day has been advocated, but since loperamide is circulated through the enterohepatic circulation, doses as high as 12 to 24 mg at a time have been suggested to be required in patients with resection of the terminal ileum. Some authors advocate the possibility of raising the dosage up to 64 mg/day, considering loperamide may widen the QRS after 18 mg/day, so a strict cardiologic check is needed!

4 – Opiates increase duodenal muscle tone and inhibit propulsive motor activity. This may retard accelerated gastric emptying and prolong intestinal transit time which may benefit some SBS patients. Some anti-diarrheals (mainly codeine, diphenoxylate, and opium) may have central nervous system side effects (e.g. sedation), and they may have potential for addiction. Usually used after and in combination with loperamide.

5 – Intestinal growth factors should be considered in an SBS patient requiring TPN continuation, if that patient is stable after a period of post-surgery intestinal adaptation, which is usually the case twelve to 24 months after the last intestinal resection and in the absence of contraindications. Drugs are now under phase III clinical studies (somatotropin or teduglutide), and they are believed to increase the risk for gastrointestinal neoplasias, so close screening is demanded. Intestinal growth factors shall be only prescribed by experts who are experienced in the diagnosis and management of SBS. New molecules are under new studies (Glupaglutide and Apaglutide) to implement the drug’s biodisponibility and reduce daily administration.

Surgical Options (no transplant)

Surgery has a big responsibility in SBS, it can prevent, mitigate, or reverse the intestinal failure.

Once the patient is stabilized, reconstruction of gastrointestinal continuity should be prioritized whenever feasible by ostomy reversal and recruitment of distal unused bowel. In a large series of 500 patients with PN-dependent IF from a highly specialized center, definitive autologous gut reconstruction was achieved in 378 (82%) patients, often requiring complex and combined procedures including primary reconstruction, interposition of alimentary conduits, intestinal/colonic lengthening, and reductive/decompressive surgery.

We can divide surgical options into 4 categories:

1 – Operations to improve intestinal motility in cases of dilated bowel:

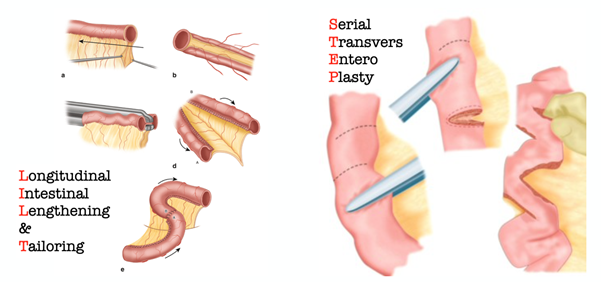

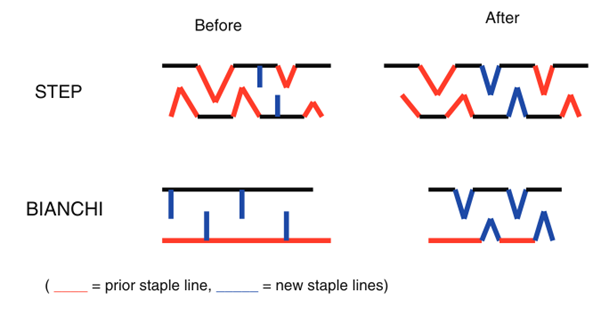

Longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (LILT) operation was first described by Adrian Bianchi, and it accomplishes intestinal tapering without loss of surface area. In the LILT procedure, an avascular space is created longitudinally along the mesenteric border of a dilated loop of bowel. The bowel is then split lengthwise. Each side of the split bowel is then tubularized, generating two “hemi-loops” that are anastomosed end to end in isoperistaltic fashion. When completed, LILT creates a loop of bowel that is twice the length of the original and half the original diameter. This is usually done in children.

Tapering without loss of surface area is accomplished effectively and relatively simply by the serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) procedure described by Kim et al. in 2003. In the STEP procedure, the intestinal lumen is narrowed by firing a series of staples perpendicularly to the long axis of the bowel in a zig-zag pattern without interfering with the blood supply of the bowel.

The choice of lengthening procedure between the Bianchi LILT and the technically simpler STEP remains somewhat unclear and until recently seemed related to surgeon preference.

2 – Operations to slow intestinal transit in the absence of bowel dilatation:

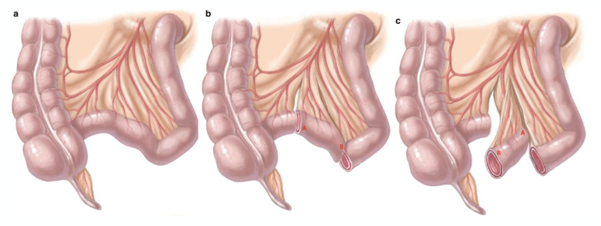

Among the possible surgical operations, segmental reversal of the small bowel (SRSB) shows the greatest promise. SRSB creates an antiperistaltic segment of bowel approximately 10-12 cm in length, located approximately 10 cm proximal to an end-stoma or small bowel-colon anastomosis. Of 38 patients undergoing SRSB over a 25-year period at a single center, 17 (45%) achieved complete independence from PN. Among patients who were not weaned, PN requirements were decreased by a median three days per week.

3 – Operations to correct slow transit:

These situations are relatively rare and should trigger a search for strictures, partial obstructions or blind loops, and enteroenteric fistulas. Often sequelae of the underlying disease leading to SBS, such as Crohn’s disease or radiation enteritis, and often require meticulous investigation to diagnose and treat appropriately (stricturoplasty or fistulectomy are the most frequently required).

There are some particular cases where the bowel length is sufficient but the dilatation prevents a correct patient’s nutrition with vomits, diarrhea and abdominal pain. Here a conventional bowel tapering with partial reduction of bowel lumen can improve patient’s symptoms allowing a correct alimentation.

4 – Operations to increase mucosal surface area:

Although the creation of neomucosa remains an elusive goal, use of sequential lengthening procedures and controlled tissue expansion (CTE) before bowel lengthening may have immediate, albeit limited, clinical application. The Manchester experience with CTE, limited to only ten cases where a LILT or a STEP procedure where followed by a second STEP operations achieving small bowel lengthening and independence from TPN in 43% of patients after the first reSTEP and an additional 21% after a second reSTESP. The “costs” are high, morbidity was 64% with no deaths, but 36% of patients underwent intestinal transplantation at 2 years.

To summarize, management of IF requires a multidisciplinary approach to optimize intestinal rehabilitation and overall patient outcome. Although ITx (Intestinal Transplant) remains a good option for patients with severe life-threatening complications, autologous intestinal reconstruction appears the better overall option. The surgical approach should integrate the age of the patient, intestinal status (dilated or non-dilated small bowel remnant), and experience of the center.

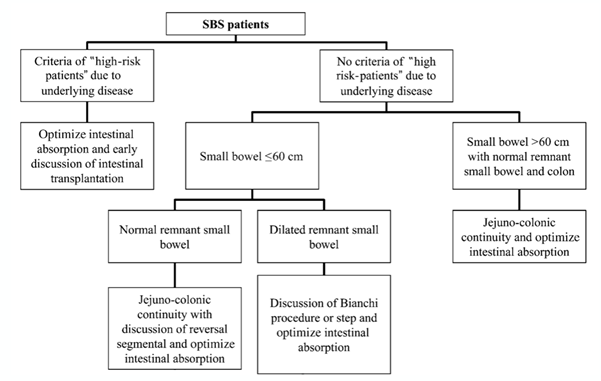

Luckily for us this 2013 diagram from Dr Layec help us out when we have to decide which kind of surgery we may offer to each patient:

Intestinal Adaptation

This term try to include every change (spontaneous or induced with diet, conventional drugs and non-transplant surgery) that will happen in a SBS patient which may lead to intestinal failure reversibility with weaning off HPN.

This process may last up to 3 years after last intervention and has a success rate of 20%, 40% and 80% in SBS-type 1, SBS-type 2 and SBS-type 3, respectively.

If the remnant bowel is healthy, the probability of SBS-CIF reversibility is higher when the length of the remnant small bowel in continuity is >100 cm in SBS-type 1, >65 cm of small bowel in SBS-type 2 (provided that there is >50% of colon in continuity), and >30 cm in SBS-type 3.

These adaptations are thanks to decrease intestinal motility, intestinal mucosa hyperplasia and increase of Short-Chain Fatty Acids colonic production.

There is still one point of uncertainty: how these patients will absorb other pharmacological therapy, like antibiotics or painkillers, so far we have no studies on this specific aspect.

Intestinal Transplantation

Patients with IF should be assessed for candidacy for ITx, when they have been evaluated by a multidisciplinary team, rehabilitation options have been explored, and a state of permanent/irreversible or life-limiting IF, and one of the following exist:

- Evidence of advanced or progressive IFALD (Intestinal Failure Liver Disease), as described below:

- Hyperbilirubinemia >75 mmol/L (4.5 mg/dL) despite intravenous lipid modification strategies that persists for >2 months;

- Any combination of elevated serum bilirubin, reduced synthetic function (subnormal albumin or elevated international normalized ratio (INR)), and laboratory indications of portal hypertension and hypersplenism, especially low platelet count, persisting for >1 month in the absence of a confounding infectious event(s).

- Thrombosis of three out of four discrete upper body central veins (left subclavian and internal jugular, right subclavian and internal jugular);

- Invasive intra-abdominal desmoids;

- Acute diffuse intestinal infarction with hepatic failure;

- Failure of first intestinal transplant;

- Any other potential life-threatening morbidity.

Intestinal transplant is a very complex operation done by few centers worldwide, thanks to the international registry of intestinal transplantation (last update 2023) we know that worldwide more than 60% of the ITx are done due to small bowel syndrome.

Often patients are evaluated for a double liver-bowel transplant due to IFALD.

In the last 2023 update the survival patient rate at 1-year was 76% decreasing at 50% at 5-year, but the graft-survival rate was 69% at 1-year and 44% at 5-years.

In conclusion, as written before in the intestinal adaptation paragraph, the intestinal transplant should be used as the last resource.

Taking the best sum-up from the article of Dr Francisca Joli published in 2018 on “Five-year survival and causes of death in patients on home parenteral nutrition for severe chronic and benign intestinal failure” we can say: “The overall survival probability was 88%, 74% and 64% at 1, 3 and 5 years respectively. Survival was inversely related to age (p < .001) and higher in patients with Crohn’s disease or chronic idiopathic pseudo-obstruction. A total of 169 (36.5%) patients were weaned-off HPN (Home Parenteral Nutrition) mainly (80%) within the first year and most frequently in patients with fistulae. Five of the 14 patients who underwent ITx died. By the end of the study, 104 (23%) of patients died on HPN; 65% of deaths occurred within the first 2.5 years of HPN.” To make it simple, ITx isn’t always the best choice…

This has been a long journey, small bowel syndrome is a quite rare situation and we hope we gave you the basics to understand it.

Few more last advices for you if you have to manage a patient with SBS:

- Refer him or her to a specialize center with a multidisciplinary team;

- First surgical option is to rebuild jejuno-colonic continuity;

- Consider intestinal transplantation as a last resort;

- Autologous intestinal reconstruction options must be considered before ITx and planned according to:

- Age and patient frailty

- Intestinal status

- Center experience

- Pros and cons for each technique

As always, we really hope this will help you out!

See you all soon…

Namasté!

References

- Carlson GL. Surgical management of intestinal failure. Proc Nutr Soc 2003;62:711-8.

- Sudan D, et al. Comparison of Intestinal Lengthening Procedures for Patients With Short Bowel Syndrome. Ann Surg 2007;246:593-604.

- Andres AM, et al. Repeat Surgical Bowel Lengthening With the STEP Procedure. Transplantation 2008;85:1294.

- Jones BA, et al. Report of 111 consecutive patients enrolled in the International Serial Transverse Enteroplasty (STEP) Data Registry: a retrospective observational study. J Am Coll Surg 2013;216:438-46.

- Witte MB. Reconstructive Surgery for Intestinal Failure. Visc Med 2019;35:312-9.

- Pironi L, et al. Characteristics of adult patients with chronic intestinal failure due to short bowel syndrome: An international multicenter survey. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2021;45:433-41.

- Negri E, et al. Early Bowel Lengthening Procedures: Bi-Institutional Experience and Review of the Literature. Children 2022;9:221.

- Pironi L, et al. ESPEN guideline on chronic intestinal failure in adults – Update 2023. Clinical Nutrition 2023;42:1940-2021.

- Joly F, et al. Five-year survival and causes of death in patients on home parenteral nutrition for severe chronic and benign intestinal failure. Clin Nutr 2018;37:1415-22.

How to Cite This Post

Muñoz-Cruzado VD, Marrano E, Bellio G. Tug of War. Surgical Pizza. Published on May 17, 2025. Accessed on July 26, 2025. Available at [https://surgicalpizza.org/rescue/tug-of-war/].