Escaping Oceanic Flight 815

The words “bail out” were never, ever to be spoken in an airplane unless you meant it. I hoped I would only ever say it in our flight briefings, but this would not be the case.

Larry Brown

The vicious rolling stones strike back my friend. We’ve already made our point on acute cholecystitis diagnosis and management in previous posts.

If you’re looking at your screen scrolling through this short article, you’ve clearly ignored our last advice:

“Don’t be eager to operate on anyone…

Don’t be ready to deny the usefulness of the conservative treatment after one failure…

Don’t be a surgeon…”

Or you just played too much with your karma in a previous life…

You’re on call, at 3 pm, way too far from your escape from the hospital.

A 38-year-old gentleman, with a previous history of multiple biliary colic episodes, shows up in the emergency department complaining about RUQ intense abdominal pain onset in the last 96 hours.

He has a fever (38.1°C), vomiting, a positive Murphy sign, and Blumberg sign in the upper quadrants at the examination.

- Labs: WCC 22’000/mm3 , CRP 230 mg/L

- Abdominal US: signs of acute cholecystitis with peri-cholecystic free fluid

Since we’re good folks, we did our homework and know that this is a case of moderate acute cholecystitis. Our patient is a low-risk one and he had a good clinical response to our initial medical treatment.

The OR is available, so you schedule the gentleman for an emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

You enter the abdomen, and the gallbladder does not show up. A hard, swollen, omentum-covered bulging structure lies instead of the gallbladder.

You’re facing a grade five Parkland cholecystitis my friend. This should mean something to you, and you’re not happy about that…

So, let’s go back to the Parkland grading scale for acute cholecystitis:

- Grade 1 – Normal appearing gallbladder (“robin’s egg blue”): No adhesions present and completely normal gallbladder;

- Grade 2 – Minor adhesions at the neck or lower of the gallbladder, otherwise normal gallbladder;

- Grade 3 – Presence of any of the following: hyperemia, pericholecystic fluid, adhesions to the body, distended gallbladder;

- Grade 4 – Presence of any of the following: adhesions obscuring the majority of the gallbladder, Grade 1-3 with abnormal liver anatomy, intrahepatic gallbladder, or impacted stone (i.e. Mirizzi);

- Grade 5 – Presence of any of the following: perforation, necrosis, inability to visualize the gallbladder due to adhesions.

The grading scale has a good correlation with operative events, such as conversion rate to open surgery, operative time, and/or technical difficulty, and postoperative complications, such as biliary leak rate. Higher the grade, the higher the chances of facing a tough case with non-negligible intra- and postoperative risks.

Ok then… Back to our clinical case…

You know what you are facing and the risks correlated… So you proceed carefully with blunt laparoscopic dissection of thick omental adhesions to the gallbladder. You can finally see the fundus and the body, which appear affected by an acute inflammatory process with edema and necrotic spots; the infundibulum and the cholecystic fossa are inaccessible due to dense adhesions. You keep on trying for almost half an hour trying to get there, but instead, you keep going nowhere.

Now what?

The father of safety during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Dr. Strasberg, has something for us…

No, man… Not the classification of iatrogenic bile duct injury… For God’s sake…We are still trying to avoid that…

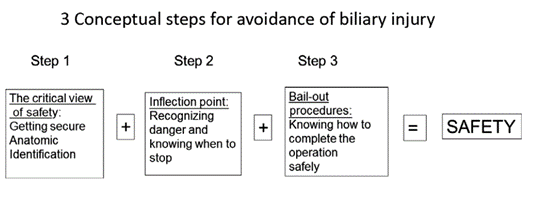

Since our mission is to avoid biliary and vascular injuries, Dr. Strasberg suggested a three-step roadmap for a safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy:

Reaching the critical view of safety (CVS) is a dynamic process, and confirmation needs a time-out during surgery which is temporarily static.

Three points are needed, citing our master:

- The hepatocystic triangle must be cleared of fat and fibrous tissue, whereas the common bile duct doesn’t need to be exposed;

- The lowest part of the gallbladder must be separated from the cystic plate;

- Two structures (and only two!!!) should be seen entering the gallbladder.

Amen…

But in the clinical case, we got stuck with an impossible fossa dissection. So, what to do?!…

We should be wise and take advantage of the inflection point, the point on a smooth plane curve at which the curvature changes sign. Translated in surgical words, when, during a surgical procedure, you find out you got stuck and you are not able to continue. This point, this epiphany moment before it is too late, is different between surgeon and surgeon…

The first step to take when you are there?!… Be humble and call for external advice after careful consultation with your assistant. Your colleague may agree with you that the moment to change the goal of the procedure has come…

To do that, we need to change our mindset… As Master Yoda would have said if he was a surgeon:

“Far better to reach the inflection point it is, than the operation with a biliary injury to end”…

Amen (part 2)…

Thus, we decided to abort our CVS mission and go for a bail-out procedure (BOP).

Remember that laparoscopy, in expert hands, is safe enough, and conversion does not add any advantage. The conversion is not a BOP, what follows the conversion may be. However, if you feel comfortable and confident in laparoscopy, then go for it.

Once you have decided which approach to use, the following step is to determine what comes next… Which BOP to use?

The ancients used to place a tube cholecystostomy followed by a challenging cholecystectomy during another procedure.

Nowadays, we have a few more options:

- Use indocyanine green to identify the common bile duct and the cystic duct (dosage and timing of administration are still unclear);

- Fundus-first approach to the gallbladder;

- Subtotal cholecystectomy;

Always remember that you may convert to open surgery!!! It is not a failure… and it is always better than ending the operation with a bile duct injury…

The most diffuse one-step BOP is the subtotal cholecystectomy (SC). The SC was introduced and studied during the first half of the 20th century. At first, it was early abandoned, only to be reconsidered after the introduction of the endoscopic approach for the control of a surgically induced biliary fistula.

“Each patient has its escape route… Be patient and you will find it!”

Uncommonly, surgeons deal with situations in which the gallbladder cannot be found, or only the top of the fundus is exposed after a trial of dissection. In these situations, the best bail-out solutions are:

- Aborting the procedure and follow-up the patients for possible further endoscopic procedures in case of a hidden gallbladder;

- The placement of a tube cholecystostomy with stone removal followed by an interval cholecystectomy in the case of unique exposure of the dome of the gallbladder.

Most commonly, the gallbladder can be completely dissected, even in Parkland’s grade 5 cases, and the hepatocystic triangle is the only region not approachable, due to thick adhesions, making it impossible to obtain a CVS. Then a cautious dissection above Rouviere’s sulcus is not feasible.

One solution could be to try to dissect the gallbladder from the fundus to the Calot, that would be like an “open” operation. If you are able to identify through this approach the cystic duct and the artery, good for you! But if you cannot achieve it, remember to keep a very low threshold for open conversion or subtotal cholecystectomy (SC).

The SC is our solution, it is a simple procedure for a complex issue.

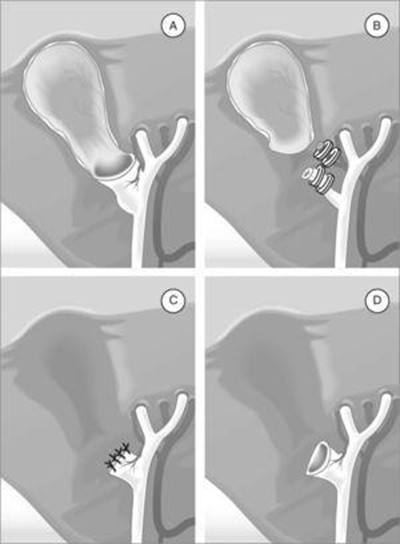

Two types of SC have been described: the fenestrating SC and the reconstituting SC.

- Fenestrating SC – The operator removes the peritoneal side/wall of the gallbladder, cauterizing the remnant, leaving the infundibulum open, or trying to close the cystic duct from the inside. The pitfalls are the risk of a surgically induced biliary fistula claiming for a postoperative biliary endoscopic procedure;

- Reconstituting SC – The solution is to close the remnant, simulating a new gallbladder, but with a higher risk of stone formation.

Whether you’ve been in the business for years or you’re a young fella’, here are some tips to perform a SC. According to Henneman and colleagues, SC can be grossly performed in four ways, as shown in the figure below.

- A. Preserving the posterior wall, leaving the infundibulum open;

- B. Preserving the posterior wall and closing the remnant;

- C. Complete removal of the body and the fundus of the gallbladder, closing the infundibulum with a continuous slowly resorbable 2/0 suture;

- D. Complete removal of the body and the fundus of the gallbladder, leaving the infundibulum open.

It would be smart to leave a pericholecystic drain… Why? Subtotal cholecystectomy is not always straightforward, and sometimes further procedures are needed.

What to expect after a SC? Some patients can develop a biliary fistula which can resolve spontaneously or require an ERCP along with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Others will surprise you by developing a bile collection that may evolve into an abscess requiring drainage or surgical revision.

We hope we were able to prove to you there are many arrows in our quiver to help us come out from difficult intraoperative situations during cholecystectomies… You just need to know them, and convince yourself that using them is not a failure…

My wife always says to me: “if you don’t know what to do, remember: less is more, but also doing nothing can be a great solution.”

Until next time…

References

- Bellio G, Marrano E. The Vicious Rolling Stones – Part 1. Surgical Pizza. Published on December 21, 2020. Accessed on August 20, 2022.

- Bellio G, Marrano E. The Vicious Rolling Stones – Part 2. Surgical Pizza. Published on January 9, 2021. Accessed on August 20, 2022.

- Lee W, et al. Does surgical difficulty relate to severity of acute cholecystitis? Validation of the parkland grading scale based on intraoperative findings. Am J Surg 2020;219:637-41.

- Madni TD, et al. The Parkland grading scale for cholecystitis. Am J Surg 2018;215:625-30.

- Strasberg SM. A three-step conceptual roadmap for avoiding bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an invited perspective review. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2019;26:123-7.

- Yildirim AC, et al. Comparison of fenestrating and reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomy techniques in difficult cholecystectomy. Cureus 2022;14:e22441.

- Strasberg SM, et al. Subtotal cholecystectomy – “fenestrating” vs “reconstituting” subtypes and the prevention of bile duct injury: definition of the optimal procedure in difficult operative conditions. J Am Coll Surg 2016;222:89-96.

- Koo JGA, et al. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: comparison of reconstituting and fenestrating techniques. Surg Endosc 2021;35:1014-24.

- Jara G, et al. Colecistectomía laparoscópica subtotal como alternativa quirúrgica segura en casos complejos. Cir Esp 2017;95:465–70.

- Henneman D, et al. Laparoscopic partial cholecystectomy for the difficult gallbladder: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 2013;27:351-8.

How to Cite This Post

Cioffi S, Marrano E, Bellio G. Escaping Oceanic Flight 815. Surgical Pizza. Published on September 24, 2022. Accessed on July 27, 2025. Available at [https://surgicalpizza.org/emergency-surgery/escaping-oceanic-flight-815/].

3 Comments

Pingback:

Yoshiro Kobe

Thank you for your interesting post.

Pingback: