The Feeling of Having Another Pit in the Stomach – Part 1

If you find yourself in a hole, the first thing to do is stop digging.

Will Rogers

Historical Background

Princess Anne Henrietta of England, daughter of King Charles I of England, was the first case of death from perforation of a peptic ulcer described in the literature in 1670. But, because her death was initially suspected to be due to poisoning, the first official report of a case of duodenal perforation due to peptic disease was described in 1688 by Muralto and Lenepneau. However, despite the suspicions surrounding his death, the expert consensus since the 20th Century is that he died of peritonitis from a perforated peptic ulcer.

In 1894, Dean described and performed the first successful surgical closure of a perforated duodenal ulcer. Cellan-Jones in 1929 described the omental patch technique as a surgical option for this type of perforation, followed by Graham in 1937 with a modified version.

The first laparoscopic repair of a perforated duodenal ulcer was reported in 1990.

Introduction

Under normal conditions, there is a physiological balance between gastric acid secretion and gastroduodenal defence. Mucosal injury leading to peptic ulcer occurs with altered stasis between aggressive factors and defence mechanisms.

Peptic ulcer is a common disease (read our previous post to learn more), with a lifetime prevalence in the general population of 5-10% and an incidence of 0.1-0.3% per year. Despite dramatic reductions in incidence, hospitalisation, and mortality rates over the past 30 years, 10-20% of these patients still develop complications. Peptic ulcer remains a major health problem, which can consume considerable economic resources. Recurrences of up to 12.2% have been reported.

Perforation is the second most common complication of gastroduodenal peptic ulcer, with bleeding being the most frequent complication. Although perforation is less frequent, with a perforation/hemorrhage ratio of about 1:6, it is the most common indication for emergency surgery and causes about 40% of all ulcer-related deaths.

Duodenal ulcer is the predominant lesion in the Western population, whereas gastric ulcers are more common in Eastern countries, with the latter having a higher morbidity and mortality.

Duodenal perforation occurs in the duodenal bulb in 62 % of cases, followed by the pyloric region. In 90% of cases, the perforation is on the anterior aspect. It is more frequent in males with an average age of 50-60 years. A mortality rate of 8-25% has been reported.

The incidence of peptic ulcer has decreased in recent years. This may be partly explained by the use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. However, we continue to encounter cases to this day. Average age in the 7th-8th decade of life and more frequent in males (1:5).

Etiology

The two most frequent causes of perforation are H. Pylori infection and NSAID abuse. In patients with recurrent duodenal ulcers, even with PPI treatment, acid hypersecretion, such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, should be suspected as a MEN1 syndrome. In addition, there are also other causes of perforation such as duodenal diverticula, autoimmune diseases, Crohn’s disease, duodenal ischemia, vasculitis such as PAN, iatrogenic, patients with active chemotherapy, drugs (e.g. corticosteroids, bisphosphonates…), and tobacco use.

Interestingly, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with a 0.015% incidence of iatrogenic duodenal injury.

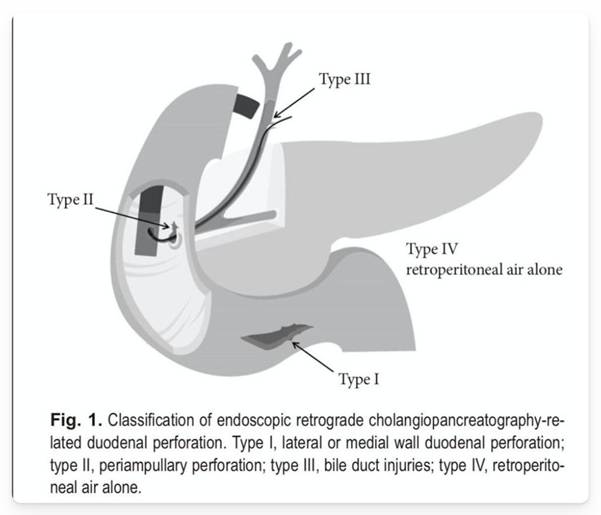

The incidence of iatrogenic lesions after endoscopy is higher in therapeutic procedures, with a reported incidence of 1.6% in cases of ERCP. The Stapfer classification is used for the description of perforations secondary to ERCP.

Diagnosis & Initial Management

The clinical presentation of gastroduodenal perforation is usually a sudden onset of abdominal pain. Localised or generalised peritonitis is typical of perforated peptic ulcer, but it is usually present in only two-thirds of patients. Thus, physical examination findings may be equivocal, and peritonitis may be minimal or absent, particularly in patients with a contained and/or sealed leak.

Classically, the clinical presentation of duodenal perforation is divided into three processes: initially the patient complains of severe epigastric pain, then over hours (2-12 hours) the pain migrates to the lower hemiabdomen/right iliac fossa area (i.e. Valentino’s syndrome), and after 12 hours fever, signs of hypovolaemia and abdominal distention may occur.

Early recognition of sepsis (i.e. before the onset of organ dysfunction) is a priority. During the evaluation in the emergency department of any septic patient, several elements should be taken into account to assess the clinical picture. In particular, several symptoms (i.e. altered mental status, dyspnoea), signs (i.e. tachycardia, tachypnoea, decreased pulse pressure, decreased urine output) and laboratory findings (hyperlactatemia, arterial hypoxaemia, increased creatinine, coagulation abnormalities) should be evaluated. It is important to keep in mind that these findings may be modified by pre-existing diseases or medications; for this reason, careful history taking should be performed.

Scoring systems such as sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) or rapid SOFA (qSOFA) are available to assess disease severity, with associated limitations.

Patients with unstable perforated peptic ulcer require adequate and rapid resuscitation (ideally within 1 h) to reduce mortality. First, as in any emergency situation, a rapid ABC (airway, breathing, and circulation) assessment should be performed. Secondly, appropriate targets for resuscitation (the same as those used for sepsis and septic shock) should be considered.

In general, the most important are:

- Mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mmHg

- Urine output ≥ 0.5 ml/kg/h

- Lactate normalisation

Laboratory tests are non-specific, although leukocytosis, metabolic acidosis and elevated serum amylase are often associated with perforation.

The first complementary diagnostic test is a chest X-ray, possibly in an erect position, to detect the presence of pneumoperitoneum. The presence of this radiological sign is highly variable in the different studies in the literature and ranges from 30 to 85% of perforations. It needs to be always remembered that a negative X-ray does not rule out a possible perforation. This is why many authors advocate that the first radiological examination to be performed is a contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan. However, up to 12% of patients with perforations may have a normal CT scan. In this scenario, administration of oral or nasogastric tube water-soluble contrast and performance of triple-contrast CT may improve diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.

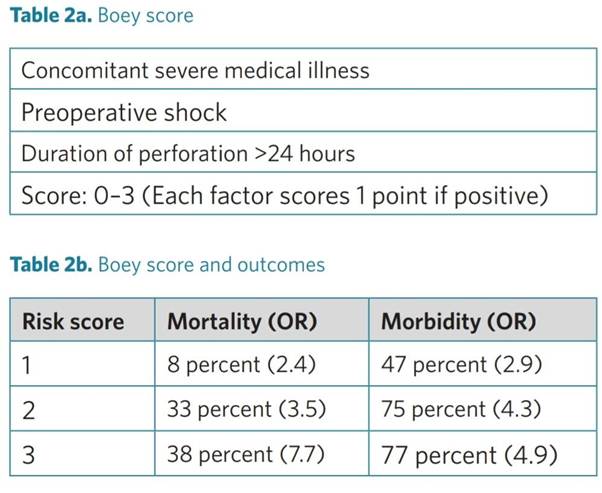

In patients with perforated peptic ulcer, it is suggested to adopt scoring systems (e.g. the Boey, PULP and ASA score) to stratify patient risk and predict outcome.

Numerous scoring systems have been designed and validated to predict mortality and morbidity in patients with perforated peptic ulcers. The Boey score is the most widely used, followed by the ASA score and the PULP score. The Boey score showed a high variability in accuracy in the different studies in which it was tested. On the other hand, the PULP score is difficult to apply and has not yet been validated.

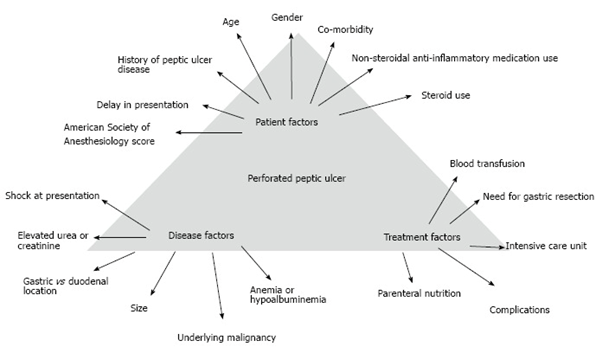

The following picture describes the multiple factors that influence the prognosis of these patients.

H. pylori infection is present in 70-90% of patients with duodenal ulcers, which is why H. pylori testing should be performed in the evaluation of these patients.

Initial Treatment

When a diagnosis of duodenal ulcer perforation is made, fluid therapy, intravenous antibiotics, analgesia, intravenous PPI, positioning of a nasogastric tube and a bladder catheter should be initiated. Kin Tong et al. describe that treatment with omeprazole IV should be performed for 72-90 hours, and then H. Pylori eradication treatment should be started, thereby reducing recurrence.

Non-Surgical Treatment

Conservative treatment may be considered in cases in which there is a contained perforation without evidence of contrast leakage in imaging tests.

Conservative treatment ‘Taylor method’ (described in 1946 by Hermon Taylor) consists of nasogastric tube placement, serum therapy, antibiotics, and repeated clinical evaluation. An oral gastrografin study is essential to confirm the absence of leakage in patients selected for non-surgical treatment.

The most important factors regarding the feasibility of non-surgical treatment for perforated peptic ulcer are normal vital signs in a stable patient and whether the ulcer itself is contained/sealed as confirmed by an oral water-soluble contrast study: if there is free contrast leakage, surgery is necessary. On the other hand, the non-surgical option could be considered if there is no contrast extravasation and the patient has no signs of peritonitis or sepsis.

In clinical practice, the non-surgical management strategy is resource-intensive and requires a commitment to regular active clinical examination along with the availability of a surgeon 24 hours a day and, if clinical deterioration occurs, emergency surgery is warranted.

The essential components of non-surgical treatment of peptic ulcers can be grouped into ‘Rs’:

- Radiologically undetected leakage

- Repeated clinical examination

- Repeated blood tests

- Respiratory and renal support

- Resources for monitoring and

- Readiness for surgery

Any patient undergoing non-operative management should be treated with:

- Absolute diet

- Intensive serotherapy

- SNG placement

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Intravenous antibiotic therapy (4-6 weeks of antibiotic treatment)

H-2RAs (i.e. ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine) also suppress acid secretion, although to a lesser degree, with a higher incidence of ulcer recurrence at the end of treatment. In addition, PPIs have been shown to be superior to H2RAs in reducing morbidity and mortality during non-surgical treatment of perforated peptic ulcer.

Several studies have reported a success rate of 70% with this method in selected patients. However, we must keep in mind that mortality increases with each hour of delay until surgery, so NOM must be carefully selected. Buck et al. demonstrated in a study of 2,688 Danish patients that each hour of delay from admission to surgery was associated with a minus 2.4% chance of survival compared to the previous hour. Older patients may experience paradoxically higher mortality if non-surgical treatment fails, so caution is advised in patients over 70 years of age.

In multivariate analysis, factors independently related to NOM failure were: pneumoperitoneum size (to measure this, they establish a ratio of total pneumoperitoneum size to the size of the 1st lumbar vertebra: if this ratio was greater than 1, the failure rate was 60.5%), heart rate > 94 bpm, and abdominal meteorism (defined as distended bowel loops).

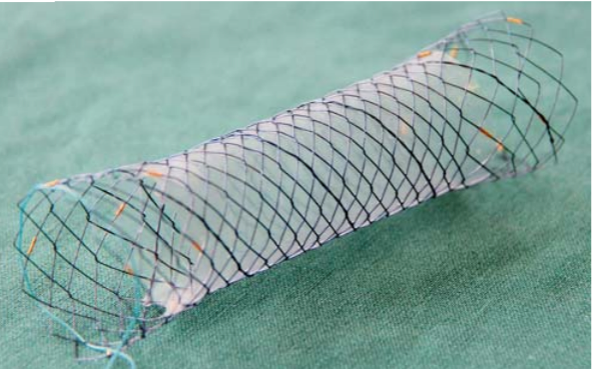

In addition to the conservative approach described so far, closure of acute iatrogenic perforations with endoscopic clips has been described. However, clips may not be effective in cases of perforated ulcer due to fibrotic tissue with loss of distensibility. In addition, combined laparoscopic-endoscopic approaches for closure of perforated ulcers have also been described. Bergstrom et al. present a case series of eight patients with perforated duodenal ulcers treated with self-expanding metal stent grafts and the results indicate that, in very selected patients or in cases where surgical closure is anticipated to be difficult, gastroscopy with stent placement during laparoscopy, followed by laparoscopic drain placement, could be performed. In patients with severe comorbidity or late diagnosis, gastroscopy and stenting followed by radiologically guided drain placement could be an alternative to more standard treatment. Endoscopic omentum sequestration and traction are also described as an effective adjunct to duodenal plication.

Endoscopic Treatment

In patients with perforated peptic ulcer, it is suggested to avoid endoscopic treatment such as clipping, fibrin glue, or stenting.

The standard treatment of perforated duodenal ulcers is laparoscopic or open surgery with primary closure, in most cases with good results. However, advanced age, comorbidity, shock, and delayed treatment are factors associated with increased mortality. In these settings, stent treatment of perforated duodenal ulcers is feasible and safe. Although the patients had severe comorbidities, seven out of eight recovered.

Stenting and primary drainage have proven to be an effective and safe method of treating esophageal perforations. The same technique is increasingly used to treat anastomotic leaks after gastric bypass surgery, with good clinical results. Following these experiences, the treatment of perforated duodenal ulcers with self-expandable metal stent grafts (SEMS) was attempted.

The study from Bergstrom et al. presents a case series of eight of eight patients with perforated duodenal ulcers with SEMS. The first two patients received stents due to postoperative leaks after initial traditional surgical closure. All six patients received SEMS as primary treatment due to comorbidities or surgical technical difficulties.

In this study, they conclude that metal stent grafts can be used as an alternative treatment for perforated duodenal ulcer in patients with advanced age, comorbidities, late diagnosis or difficulties in primary closure of the defect. Simultaneous drainage of the abdominal cavity at the site of the leak appears to be crucial in most cases. Stent treatment together with percutaneous drainage may even be a future alternative to surgery in all patients with perforated duodenal ulcers. They describe the removal of the stent after 30 days.

Ok guys, let’s stop here for now.

Next time, we will focus on the surgical treatment of this challenging disease.

References

- Barmparas G, et al. Empiric antifungals do not decrease the risk for organ space infection in patients with perforated peptic ulcer. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2021;6:e000662.

- Tarasconi A, et al. Perforated and bleeding peptic ulcer: WSES guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2020;7:15:3.

- Songne B, et al. Non operative treatment for perforated peptic ulcer: results of a prospective study. Ann Chir 2004; 129:578-82.

- Chung KT, et al. Perforated peptic ulcer – an update. World J Gastrointest Surg 2017;9:1-12.

- Buck DL, et al. Surgical delay is a critical determinant of survival in perforated peptic ulcer. Br J Surg 2013;100:1045–9.

- Joshi MA, et al. Treatment of duodenal peptic ulcer perforation by endoscopic clips: A novel approach. J Dig Endosc 2017;8:24.

- Bergstrom M, et al. Self-expandable metal stents as a new treatment option for perforated duodenal ulcer. Endoscopy 2013;45:222-5.

- Bucher P, et al. Results of conservative treatment for perforated gastro-duodenal ulcers in patients not eligible for surgical repair. Swiss Med Wkly 2007;137:337-44.

How to Cite This Post

Galofré C, Protti GP, Bellio G, Cioffi SPB, Marrano E. The Feeling of Having Another Pit in the Stomach – Part 1. Surgical Pizza. Published on June 22, 2025. Accessed on December 29, 2025. Available at [https://surgicalpizza.org/emergency-surgery/the-feeling-of-having-another-pit-in-the-stomach-part-1/].